Rebirth of The Band: 1970s

Rebirth of The Band: 1970s

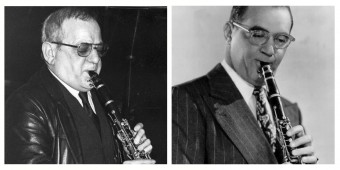

Diminutive, dapper and bespectacled, Steve Morris was a Benny Goodman look-alike who, like Goodman, played jazz clarinet. But, unlike the famous and reputedly arrogant Goodman, Steve was a modest and mild-mannered man, though he shared Goodman’s love of music and his desire for a world without prejudice, whether of race, religion or class.

More than a glimpse, a little capsule, of that ideal world was created by Steve when, like his old musician friend Ronnie Scott, he fulfilled his dream of running a jazz club, one that would become internationally renowned.

LEFT: Steve Morris, “King of The Band,” born 1920, died 1991RIGHT: Benny Goodman, “King of Swing, born 1909, died 1986

When Steve, with business partner Frank Cusick, took over Band on the Wall in 1975, the big old pub was closed and shuttered, almost derelict.

The early 70s had seen the venue’s decline. Whether cause or consequence of that decline, there had been no fewer than six different landlords in the first three years of the decade (1): never a good sign. The venue’s reputation as a place for classy live music had already diminished when the almost-final tacit occurred following the closure of the nearby, vast Smithfield Market that for over 150 years had sustained the vitality and economy of the locality. Throughout all of those years, Band on the Wall, formerly the George & Dragon, had been a market pub. With the move of the Market out of the city centre in 1972 (2) the pub lost a substantial customer base – thirsty market traders, their suppliers and customers.

Band on the Wall was now on the fringe of a fringe of the city: in ‘an overlooked district, languishing in a state of economic inertia.’ (3). By the early 70s, live music at the pub had become irregular and rarely notable and, in 1974, the music ceased, the venue was closed, perhaps for the first time in its 170-year history. (4) The troubled owners of the pub, Wilsons Brewery, offered the lease on the open market. But, given the loss of custom from the Market and the poor condition of the building, there was no bidding battle for the lease; not for the last time, the demise of the venue looked imminent.

For Steve Morris this was the opportunity he had been looking for, and in 1975 he grabbed the chance, taking a lease on the building in Manchester’s Swan Street. Steve had been brought up in the area – where his father had been an illegal bookmaker — and had worked as a musician in the city and abroad. Having helped run clubs for others, he had long cherished the idea of having his own jazz club. Frank Cusick, with his wife Anne, also had small business experience; the Cusicks moved into the living accommodation on the first floor of Band on the Wall, now the offices of Inner City Music. Frank was licensee in the early years and Anne worked the box-office. With limited funds, Steve and Frank carried out internal and external redecoration of the building, installed an aged grand piano and a sound system that, even for the period, was primitive. A drummer friend of Steve’s, Allan Tattersall, built the stage, in place of the platform on the wall where the resident band had previously played and that, in the 1930s, had inspired the venue’s name, colloquially further reduced to ‘The Band.’

On most weekend evenings for the next four years Allan would have a special place on the stage that he built — as drummer and leader of the resident band.

The Music

- Steve Morris’s jazzy selection

- Regular Thursdays booked by the Jazz Centre Society, from 1976

- New Manchester Review Monday Rock Club, 1977 to 1980

- Weekly promotions by the newly-formed Manchester Musicians’ Collective, 1977 to 1979

There was also occasional lunchtime theatre and comedy, including by future stars Rik Mayall and Ade Edmondson.

These programme strands are explored in more detail in the subsequent sections of this chapter.

The programme occupied different music territory from the pop hits of the day, late 70s songs such as David Bowie’s ‘Fame,’ Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody,’ ABBA’s ‘Dancing Queen’ or ‘YMCA’ by the Village People. The venue was immune even to disco hits such as ‘Stayin’ Alive’ by local boys The Bee Gees. Only with occasional punk rock and soul/funk bands on the New Manchester Review nights and those by Manchester Musicians Collective did the Band on the Wall programme in the 1970s encroach on the margins of the pop music of the day. ‘The Band’ was not about fashion.