The Tyson Era: 1937 – 1949

The Tyson Era: 1937 – 1949

The horse and trap jogged daintily out of the courtyard across the road from the George and Dragon pub that recently had acquired the curious colloquial name of “Band on the Wall,” often abbreviated to “The Band”. On board the trap: children, delighted once more to be going to school in some style. Holding the reins: the children’s father, the soon to be famous, even notorious, landlord of the pub, Ernie Tyson.

After the school run, next task for animal lover Ernie was to feed his many pets, described later by daughter Anne as a menagerie, on the flat roof of the pub.[i] There were chickens, pigeons, rabbits, parrots and parakeets, and, inside the family’s living quarters on the first floor of the pub, his two German Shepherd guard dogs.

This is Swan Street, Manchester, in the early years of World War 2.

In 1937 ex soldier, labourer, miner and occasional boxer Ernie Tyson took over the tenancy of the market pub, adjacent to Smithfield Market, one of the biggest meat, fish, fruit and vegetable markets in Europe. The pub earned the name Band on the Wall after Ernie created a high platform on the far wall of the premises to accommodate a band of musicians.

Every Christmas, including through the war years, big-hearted Ernie would throw a party at the pub for dozens of local children and he and the family would prepare gifts for all the children. Years later, Ernie’s daughter Anne, who was born at Band on the Wall during World War 2, would say of her dad:

“He was lovely… a soft pudding he was”.

Yet, in the 12 years that spanned his tenancies at Band on the Wall, Ernest Henry Tyson would generate a catalogue of stories that have given him almost legendary status. Some of these stories are still recounted a lifetime later and would rank him posthumously as a contender for Britain’s Toughest Pub Landlord:

“Fighting Tyson WAS the Band on the Wall…A law unto himself… He would have been a match for Mike Tyson” – Les Kane, Manchester resident who visited Band on the Wall in the 30s and 40s.[ii] (Mike Tyson, undisputed world heavyweight boxing champion, 1985-90)

“As rough and tough an individual as you would ever come across” – first hand account of retired Manchester police officer Dennis Wood.[iii]

“Ernie Tyson is the toughest man I have ever met. He is an ex-boxer, knuckle-fighter and Coldstream Guardsman….Nobody would try anything on when Ernie was about” – London visitor to Band on the Wall who encountered Ernie during the war.[iv]

“One punch and you’d be on the cabbages” — referring to the vegetable stalls in Oak Street outside the side door of Band on the Wall.[v]

Ernie Tyson, teenaged soldier, c1917, around 20 years prior to his tenure as licensee at Band on the Wall

Among the many stories about Tyson, two in particular underline his “fearsome reputation for violence”. The victims in both cases were overseas servicemen who frequented the pub in large numbers during WW2 and a few years after.

Policeman Dennis Wood was on his beat in Swan Street one night in the 1940s. He wrote later:[vi]

There was never a dull moment round the New Cross area, not least Swan Street where stood The Band on the Wall….During and immediately following World War 2 the hostelry had attracted thousands of soldiers, sailors and airmen from the USA and the Empire, and I have no doubt it is still discussed in far off lands today. When I had dealings with the place it was run by one of those characters whose way of life and antics were renowned. He went by the name of Ernie Tyson….

The first time I came into contact with him was one Saturday evening as I was passing the premises. He was at the front entrance and making use of every expletive known to man, in an effort to explain to two enormous American paratroopers that they were no longer welcome on his premises and that he wished them to go away. The two Yanks insisted that they were not interested in going away, and attempted to push past Ernie, and before I could intervene he struck the larger one a blow which sent him pedalling backwards across the street. He fastened his teeth into the nose of the other and began to deliver heavy blows to his stomach, until he too was released and joined his buddy in holding each other up as they staggered off along Oldham Street. Ernie nodded to me and with a grin went back into the premises.

I mentioned the incident when I got back to Goulden Street station and an old copper told me I had done the right thing in not interfering. “Ernie handles all the problems at the Band. No need for us to bother,” he said.

Another story was told by Mike Goodman who was brought up in Manchester and in the late 60s and early 70s was a taxi driver in the city: [vii]

As children and young people we were always told never come anywhere near Swan Street or the Band on the Wall, because not only the Band on the Wall but the pub opposite, the White Bear, had terrible reputations for violence, they were rough places, and they were very tribal and the people in there knew each other and didn’t like strangers, so we always avoided it. Before I was born the Band on the Wall was a favourite hang out for Canadians and Americans…

From some of his older taxi ‘fares’ Mr Goodman heard many stories about ‘hard-man Tyson’ and in 2016 he recounted perhaps the most shocking:

The story goes like this: Tyson had a fearsome reputation for violence, nobody got the better of him and one day this huge Canadian sergeant who had some kind of a needle with Tyson, wasn’t going to be hanging around, wasn’t going to be put off, and he knocked the staff out of the way and came up the stairs to get Tyson in his living quarters, you know he was that angry, Tyson stayed at the top of the stairs watching him come up, saying things like don’t come up you can’t come up here, like pretending in a way to be frightened or discomfited and when this Yank got to the top of the stairs Tyson gave him one almighty kick that sent him, the story goes and I’m sure it’s apocryphal, that he didn’t hit a step ’til he got to the bottom and he had a broken neck. Don’t know if the guy lived or died but that was him out, completely out of action. That was Tyson. We didn’t come into Band on the Wall really until it started becoming gentrified, in the 60s and the 70s and 80s… Because its reputation was that fierce.

Our research suggests that the venue in the 1960s may not quite have been gentrified although from 1975, under the benign and musicianly management of Steve Morris, Band on the Wall would establish a trouble-free reputation that continues to this day.

In the Tyson era – 1937 to 1949 – trouble was never far away, including from some of the barrow lads from the adjacent Smithfield Market who lived in the slums of Angel Meadow, just half a mile from Band on the Wall. Norman Morrison, a waiter at the pub just before WW2, said that the waiters had to “look after themselves” and he thought that the Hamilton Gang of Barrow Boys “owned the place”[viii]. Leader of the gang Jazzer Hamilton was known to visit the pub and on at least one occasion sang a love duet with one of the resident accordionists, Florence “Flo” Flanagan, who also worked as a machinist in the Swan Buildings opposite Band on the Wall. According to Flo, the gang leader had a fine singing voice.[ix]

Children’s Playground

Despite the notorious gangs and frequent trouble, the immediate vicinity was an exciting place for the Tyson children, and the Band on the Wall a memorable home.

Daughter Anne:[x] “As a child it was just so fascinating” to be brought up at Band on the Wall. She would wake to the sounds of the Market, the bustle of the traders, the clip-clop of horses. She and her sisters used to play on the flat roof of the pub or in the Smithfield Market. Sometimes they would get into trouble in the Market, though nothing serious. But on one occasion her two sisters overstepped the mark in some way and were locked up in the police cell that was in the Market. A policeman came to Ernie and asked if they should be let out. He said No, he wanted them to learn their lesson, and they stayed imprisoned until the morning.

Part of the bustling Smithfield Market at the back of Band on the Wall, 1907 — courtesy Manchester Archives & Local Studies

Born at Band on the Wall in February 1941 – in what is now Tuition Room 2 — Anne lived in the pub with her parents, Ernie and his second wife Sarah-Anne, for most of her first eight years. On occasion, while her parents prepared the pub for opening, she would see the musicians rehearse but mostly she heard the music from the first-floor living accommodation. The family’s living room was directly above the stage and dance-floor. From her bedroom overlooking Swan Street, Anne frequently heard more than music — the sound of smashing glasses and shouting as fights broke out downstairs. But the music went on: the musicians were under strict orders to continue playing, however fierce the fighting.

Christmas Blitz

The musicians also kept playing when air raids hit Manchester. The worst of these, known as the Christmas blitz, occurred in 22-24 December 1940 when a total of 443 bomb raids hit the city. More than 750 people were killed and extensive damage was caused. One bomb hit homes about 200 yards from Band on the Wall, killing two people. There was substantial damage to the Smithfield Market buildings and a fire started on the roof of Band on the Wall when some incendiary material struck the building. At the time, Mrs Tyson was eight months pregnant with Anne.

Throughout the war years, the pub normally opened at 5 am for the market people; it was “crammed” in these morning sessions, according to a young brewery employee who carried out repairs in the beer cellars of the pub from 1945 to 1949. The afternoons were much quieter and Ernie would often close up for a couple of hours in the afternoon to have a nap before opening for the busy late afternoon and evening session. On Sundays the pub was closed and from time to time Ernie and his wife went out for the evening. One Sunday, when they were at the cinema, Anne – who could have been no older than eight — heard heavy knocking at the side door. She went downstairs to the door and from outside heard “It’s the police”. She opened the door and policemen came in. They wanted a drink, not an unusual request in these days from the officers on the local beat. Anne recalls going behind the bar and, standing on a beer crate, served the policemen. When Ernie returned “He was furious, I had to run for it,” said Anne.

Not for long was Anne the only child living at the Band on the Wall. Ernie’s two daughters by his first marriage, Rose and Ivy, came to live there in 1941, shortly after Anne was born. Rose was born in 1922, Ivy in 1924; both had been living with Ernie’s mother in the few years before moving to Band on the Wall. In the years that followed, the patter of tiny feet would crescendo at Band on the Wall as more Tysons were born: Monica, Catherine and Ged. Both Rose and Ivy got married in the war years and left home, so in 1949 at the end of the Tyson Era at The Band, the family numbered six.

The Three Brothers

Ernie was one of three Tyson brothers and all three held the licence for Band on the Wall at different times in this period. Ernie was the eldest and was licensee for nine of the 12 years of the Tyson era, with Henry stepping in for seven months and Matthew for two and a half years. On some busy nights, all three would work the pub. According to Ivy, the three stopped many fights. “The three brothers were all big men who stood back to back in settling fights” but on one occasion she saw her father brought to the ground by a Canadian serviceman who had jumped on his back:

“I stood there and thought my dad would be mad, but no. He asked who had done it and when he found out he went over and shook the guy’s hand and said ‘You are the first guy to ever floor me’ and gave him a beer.

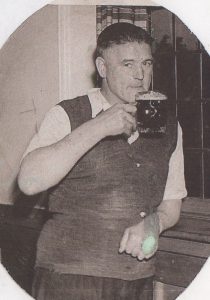

Henry, one of the three tough Tyson brothers

Wartime romance

Ivy told this story in a transatlantic letter in 2007. Then, aged 83, married name Mrs Ivy Harper, from her home in Ottawa, Canada, she told of romance and tragedy in her 20s.

Ivy was a teenager when she moved to Band on the Wall. It was there that she met Bill, a young Canadian soldier, and soon they married. But six months later, he was killed, not in action but when the Jeep he was travelling in overturned in England. He was one of over 1.1 million Canadians who served in WW2; 44,000 died.

Her letter was to the Manchester Evening News, in response to an article in the newspaper[xi] that she had been sent about the forthcoming reopening of Band on the Wall. Accompanying the article was a photograph taken inside Band on the Wall – see below.

Band on the Wall c1946

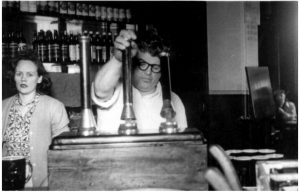

Ivy was able to identify for the first time the stockily-built man standing in the above photo as her uncle Matt Tyson and also that she was the young woman standing nearby. She wrote that she would have been aged 23 in the photo. This would put the date at 1947, though in a subsequent letter she said she left for Canada in 1946. She also wrote that she was aged eight when she first “sang with the band”; but this would place that date at 1932 – several years before Ernie and family moved to Band on the Wall.

After her young husband’s death, Ivy visited his family in Ottawa and stayed there. Subsequently, and apparently by chance, she met another Canadian serviceman, Gordon Harper whom she knew from Band on the Wall where he had worked part-time as a waiter. They married in Ottawa where Ivy stayed until her death in 2012.

How Ernie ran ‘The Band’

Ernie Tyson was “a law unto himself”[xii] and the way he ran Band on the Wall was, at best, unorthodox. “He was the boss. Everybody had to do what Ernie said,” according to Stanley Foster who, as a teenaged apprentice bar fitter for the brewery Walker & Holmfray, encountered Ernie many times in the late 1940s. Speaking in 2017, Stanley, aged 85, remembers Ernie as a rough and tough character whose mother was also formidable; he described her as a very unpleasant woman who visited the pub regularly for dinner, prepared and silently brought to her by Ernie’s wife, Sarah-Anne. Stanley said she would then “gorge her meal, as though food was going out of fashion” and amble off without a word. She kept barrow carts in a nearby lock-up and hired them to the local barrow boys.[xiii]

Ernie was “well in with the brewery,” added Stanley, partly because he regularly sent parcels of food to the brewery’s local bosses – well-received gifts in these years of strict rationing.

During the War, in the extensive windowless cellars of the pub Ernie placed several beds. There he installed Canadian deserters who earned their keep working behind the bar, and as waiters and door staff. If any deserter was troublesome, Ernie would not hesitate to inform the authorities; it was unexceptional to see Military Police enter the pub and arrest servicemen.

Ernie introduced his own, distinctive methods to speed up beer turnover in the busy pub. He kept a big tin bath of beer in the cellar from which numerous bottles were filled. Reports from that time say that piles of filled bottles were stacked in high pyramids, with plywood sheets between each tier. Customers, when first sitting at tables “were surprised to have six or a dozen bottles put before them and ‘Pay up or Leave’; Ernie gave you no choice”.[xiv] This brusque treatment seemed to work, with beer sales at times reaching prodigious levels: the pub’s record one Bank Holiday weekend was said to be 24 thousand bottles of beer consumed on the premises.[xv]Ernie bolstered his income in other ways: from time to time he would organise bare-knuckle boxing matches at Band on the Wall, charging admission, refereeing the fights himself and perhaps acting as illicit bookmaker. He also used to have “quite a good black market” operating from the pub, said daughter Anne and added that Ernie was “a wealthy man for these times,” with a stylish car as well as his horse and trap.[xvi]

Ernie Hospitalised

The low point in Ernie’s tenancy of Band on the Wall occurred one night in the mid-1940s. The details are sketchy but we know that a disturbance of some kind broke out among a small group of customers – not an unusual occurrence in the pub – and Ernie intervened and, as was his custom, forcefully ejected those he saw as the culprits. At the end of the night after customers had left, Ernie went outside to check that all was clear, and was jumped on by the men he had ejected.

Daughter Anne who was probably just five at the time learned that her dad had been badly beaten. She said later: “It was very serious: he was nearly finished”[xvii]. She said he spent six to 12 months in hospital. That was when brother Matthew, who was also an experienced publican, took over the licence of Band on the Wall. Eventually, after his hospital treatment, Ernie had stints as landlord of other, less troublesome pubs. One was The Swan, Crumpsall, which, we are told

“had a beautiful bowling green. When the bowlers came to play they found that Ernie had installed three donkeys and three tons of sand for a kids playground causing uproar in crown green bowling circles”.[xviii]

.In 1948 Ernie took back the licence of Band on the Wall from his brother Matthew. But “he was never the same,” according to Anne. And just 14 months later, he and his family left the pub for the last time. Anne said that the family then moved to a shoe shop “but it didn’t last very long” and he returned reluctantly to the licensed trade.

Ernie Tyson and wife Sarah-Anne behind the bar at Band on the Wall, late 1940s

Ernie Tyson and wife Sarah-Anne behind the bar at Band on the Wall, late 1940s

Ernest Henry Tyson died suddenly on the morning of 22 October 1951 while landlord at the King’s Arms pub on Great Ancoats Street. He was aged just 51. His brothers, who both had been publicans in Salford, both died at age 54, Henry in 1956 and Matthew in 1962. In early 1940, during his short spell as licensee of Band on the Wall, Henry also held the licence at The Clowes Hotel, Trafford Road, Salford. At this time he was a member of the ARP (Air Raid Precautions) rescue squad but was fined £5 for “showing a light”during blackout.

Ernie’s Legacy

Almost without exception, the numerous stories of Ernie Tyson are about his fearsome reputation, of fisticuffs and tough-guy incidents. But there is much more to Ernie’s tenure at the pub than the subject of lurid stories: perhaps more than anyone he created Band on the Wall — a place open to all and renowned for music (and good times).

It was Ernie who in 1937, shortly after he had taken the licence, created the high stage or shelf for the musicians that led to the renaming of the pub as Band on the Wall. Today this might be regarded as a marketing masterstroke: would the venue have captured peoples’ imaginations if it had retained the ubiquitous English pub name of the George and Dragon? Some say it was Ernie’s decision to call it Band on the Wall; others claim that customers gave it that nickname. Whichever, it permanently linked the venue’s name to the music.

According to a musician who performed there in the late 1930s, it was Ernie who decided on a resident band of five musicians.[xix] This was a step up from the more ad hoc arrangements that applied to musicians at most other pubs, probably also in previous years at the George and Dragon. Without doubt music had been played there for decades. There is evidence that Leslie Stuart, composer of several musicals and famous songs such as ‘Lily of Laguna’ and ‘Soldiers of the Queen,’ played piano at the George and Dragon, probably in the late 19th century[xx]. Indeed in Victorian times the soundscape of the bustling surrounding area was frequently filled with the lively contributions of street musicians, barrel organs and of instrumental music and sing-alongs from many pubs. Nearby ‘Little Italy’ was the leading centre of production of barrel organs and hurdy-gurdies; in Swan Street there were two piano manufacturers; one in every three of the hundreds of migrant Italians to the area was said to be a musician, many of them accordionists. One of them, the great Rudi Mancini, whose parents hired out barrel organs, got his first professional job at the George and Dragon in 1934 when he was just 14. Rudi was born in Ancoats in 1920, of Italian parents, and was employed by Ernie Tyson’s predecessor, Luke Mooney, who took over the licence on 23rd June 1932 and on the same date obtained a music license for the premises.

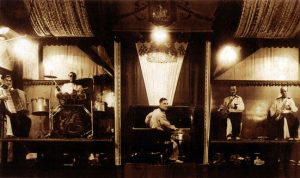

The band on stage at Band on the Wall c1937. The musicians probably include: Rudi Mancini, accordion; Jim Hart, drums; Albert Mancini, piano; one of the saxophonists known as “Mick the Pole”

Rudi’s brother Albert, an accordionist and pianist, was also a long-term member of the resident band, much of the time as bandleader. A noted teacher in Ancoats, he and Rudi started a lineage of accordion playing, beginning with Albert’s pupils Florence Flanagan and Jack Brannigan who both played Band on the Wall during Ernie’s tenancy and met at Albert’s music school. Flo and Jack subsequently married and adopted the stage name Brannelli. Their daughter Gina Brannelli is a world-renowned accordionist, teacher and international adjudicator; on the Fylde coast she created a music school for young student accordionists that continues today (2017). To date 57 UK Accordion Champions have graduated from her school.

Flo and Jack, teenage accordion stars, late 1930s.

Flo and Jack, teenage accordion stars, late 1930s.

So Ernie inherited a tradition of music at the George and Dragon, in an area of Manchester where music of some kind flourished for over a century. Ernie not only physically elevated the musicians ‘on the wall’ but also, by introducing a resident five-piece band of skilled musicians, he raised the status of the pub to that of music venue. In the Tyson era, it became “unique… a famous place”. Writer and historian Walter Greenwood wrote in 1950 that “it is known, not only at home but in many other parts of the world”.[xxi]

This international reputation was created during, and a few years after, World War 2 when servicemen, billeted in England, frequented Band on the Wall. From 1939 there were the Canadians and, after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941, the Americans. Many of them were based at the biggest airfield in Europe during the war, Burtonwood, near Warrington, that was transferred to the US Army Air Force in June 1942. Only 20 miles away, Manchester was the first choice for the US servicemen on their days off. And Band on the Wall a favourite night-spot. Visitors to the venue also included French and Australian servicemen, as well as British soldiers and airmen. Part of the attraction was the musical entertainment, also the presence of women, many from the nearby textile mills; contemporary reports also refer to it being a hang-out for ‘ladies of the night’. Ernie’s pub was open to all.

“All sorts used to pack the place every night, including opera singers from the Opera House after their show.” — accordionist Jack Brannelli, interviewed 65 years after he last played the venue.

It was also a favourite haunt of boxers, and on one occasion Ernie physically ejected former world champion Jackie Brown,[xxii] who was on an alcohol-fuelled slide following loss of his title.

Servicemen enjoyed the atmosphere of Band on the Wall, the interior of which was described by a regular as being “well-appointed”.[xxiii] It is likely that many of them found a kindred spirit in ex-soldier Ernie Tyson who was discharged from the Army before the start of the First World War. The reason: under-age; on discharge he was just 13. Then, as soon as he turned 16 he enrolled to the 5th Battalion East Lancs Regiment and subsequently served in the Coldstream Guards, reaching the rank of Lance Corporal less than a year later. On demobilization he was transferred to the Army Reserve and later spent some time in the Territorial Army.

All who entered Band on the Wall in the Tyson era could have had little doubt about the publican’s allegiance to the armed forces: centrally placed on the wall above the bandstand was a mural, about two metres in width, depicting the three UK armed services. The mural can be seen above the piano in the photo on page….

By the date of this photo, probably 1945 or 1946, the ravages of war had caused an economic decline in the area, and elsewhere; this is reflected in the set-up at Band on the Wall: in place of the previous five-piece band, there are only two musicians, no longer in uniform; the decorative drapery that adorned the stage has gone and the general décor looks tired. But the stories about Ernie had already entered Manchester folklore and, through a combination of his enterprise and the wartime circumstances, the fame of his unique music venue had spread to many lands. At its best it was a great place for musicians:

“There wasn’t a musician I knew who didn’t want to be on the Band on the Wall” – Jack Brannelli (1921-2014)

In the decades since Ernie’s premature demise, to retain the venue as a great place for musicians – and audiences – has been both aspiration and challenge for all those who follow in Ernie’s formidable footsteps.

Endnotes

[i] Mrs Anne Garner, nee Tyson, video interview, 31/3/2005

[ii] Mr Les Kane, in letter to historian Brian Holmshaw, 2000

[iii] Mr Dennis Wood, extract from book ‘A Few Coppers More’

[iv] Quote from the London Express in the Ottawa Journal October 1944

[v] Mrs Pat Mancini, interviewed June 2000

[vi] See footnote iii above

[vii] Mr Mike Goodman, audio recording, October 2016

[viii] Record held by Greater Manchester County Record Office (with Manchester Archives)

[ix] Mrs Florence Brannelli, nee Flanagan, interviewed 23/3/2005. A renowned accordionist, Flo continued playing until she was 90. She died, aged 93, in 2014, in the same year as husband Jack

[x] Mrs Anne Garner, nee Tyson, interviewed 9/12/ 2016

[xi] Manchester Evening News 29/8/2007

[xii] See footnote ii

[xiii] Stanley Foster, interviewed 22/2/2017

[xiv] See footnote ii

[xv] “Lancashire” by Walter Greenwood (1950) p171

[xvi] See footnote i

[xvii] See footnote i

[xviii] See footnote ii

[xix] Accordionist Rudi Mancini, filmed by Granada TV, 1997

[xx] Mick Burke, ‘Ancoats Lad, The Recollections of Mick Burke’

[xxi] See footnote xiii

[xxii] Mr Jack Brannelli, interviewed 23/3/2005

[xxiii] Mr Harry Beddows, to historian Brian Holmshaw, June 2000