Introduction

Introduction

The pub, the people, the area and the music in the 19th century.

The story of Band on the Wall begins over 200 years ago.

It is the reign of the mentally unstable King George III. The Prime Minister is the unimpressive Henry Addington, in place between the two terms of William Pitt the Younger. War has broken out once more between Britain and France under Napoleon who has just crowned himself Emperor. In Vienna, a 33-year-old freelance composer Ludwig van Beethoven premiers his Second Symphony to mixed reviews.

Closer to home, cotton goods have just overtaken wool as Britain’s biggest export, but there’s trouble at the mills. An economic recession is on its way and soon riots break out in Manchester and elsewhere in Lancashire; Rochdale jail will be burned down, prisoners escape and a volunteer force will be deployed against desperate Stockport handloom weavers whose jobs are being lost to the factories.

The year is 1803, the first verifiable date for the George & Dragon public-house1 – the historical name of Band on the Wall — in Swan Street, Manchester.

Less than 100 yards along the street from the nascent pub are the crossroads called New Cross, (for stories of New Cross, see Appendix 1) location of an early market shambles (mainly for meat and veg) and a kind of speakers’ corner. This is a ‘scene of riots and agitation’, fuelled by starvation wages, rising costs of bread and unemployment. There are frequent conflicts between the military and the people; cannons are placed to command these crossroads, including Swan Street. From time to time ‘shots are fired from cannon and small arms, thus wounding many of those assembled and other innocents thereabouts’2.

If in this era Swan Street sometimes resembled a battlefield, most of the time it was a place where people lived, worked and (perhaps mainly the men) drank. Presumably identifying the potential for more of the latter activity, here Elizabeth Marsh, a publican of at least eight years’ experience at another George & Dragon pub two miles away, opened the doors of what almost certainly previously was a dwelling, and traded as a pub. The lengthy and continuing story of the George & Dragon/Band on the Wall had begun.

In 1803 there was just one other pub in the street but others would follow, including those still thriving: The Smithfield Tavern (1823), The Grapes (1826) (now the Rose and Monkey) and the White Bear, now Fringe Bar.

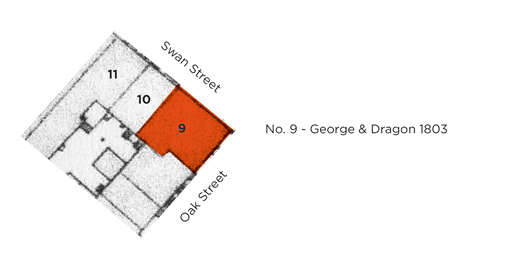

This George & Dragon, Elizabeth Marsh’s second of that name, is on the corner of Swan and Oak Streets and is small in scale, occupying around one-third of the footprint of the current main venue of Band on the Wall.

Figure 1 – The first George & Dragon

The pub is at an intersection of emergent communities that provide a large part of the labour force that would enable Manchester to become ‘without challenge the first and greatest industrial city in the world’ 3 but whose living conditions, famously studied by numerous social commentators, reformers and historians, would shock the civilised world.

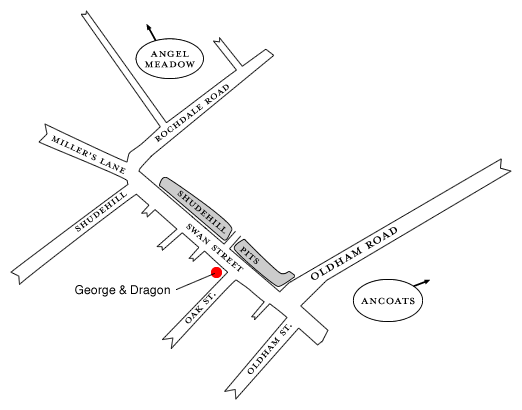

Figure 2 – Map of the area of George & Dragon.

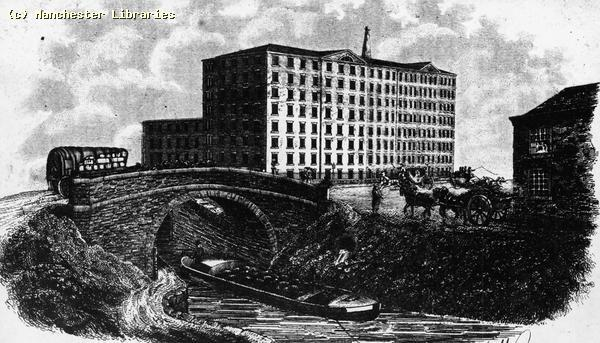

Here the George & Dragon is on the doorstep of the Industrial Revolution that would steam-power modern Capitalism, while amongst the pub’s customers are the workers whose squalid living conditions would be graphically described by reformers, including radicals who would seek to overthrow Capitalism. North, south and east, already by 1803, many of the towering structures of industry can be seen from outside the pub: already there are great, smoke-blackened mills just up the road in Ancoats and Miles Platting and down the road in Miller’s Lane where Richard Arkwright had earlier erected the first steam-powered cotton mill in Manchester4. Many more mills are under construction. The population of Manchester, at around 80,000, has trebled in the previous 25 years and industrialism is creating ‘the most fundamental transformation of human life in the history of the world’5. The little George & Dragon pub is at the locus of that transformation.

Figure 3: Mr Pollard’s Cotton Twist Mill, Great Ancoats St, 1825 (Manchester Archives & Local Studies)

Immediately across the road from the George and Dragon, along much of the length of the rough-hewn road that is Swan Street, are the Shudehill Pits, small reservoirs that for many years supplied Arkwright’s mill and other local mills with water from the River Medlock, via a series of pump engines6. A pall of smoke hangs almost permanently over the area.

The homes of the working folk are ‘blocked up from light and air,’ according to a visitor soon after Elizabeth Marsh opened the George and Dragon. ‘Here in Manchester a great proportion of the poor lodge in cellars, damp and dark, where every kind of filth is suffered to accumulate…7’

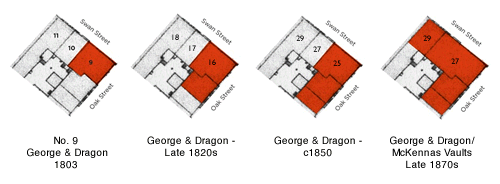

If poverty was ever-present for many of the local residents, Swan Street in the 19th century, though far from immune from the periodic ravages of recession and disease, seems never to have slipped into slumland, as did the neighbouring areas of Angel Meadow and large parts of Ancoats. Despite multi-occupancy of many dwellings-cum-workshops/warehouses, Swan Street in the early 19th century can be seen as a place of progress and betterment, of business and pleasure, its micro-economy characterised by its diversity. Throughout the century and beyond, the George & Dragon would parallel the development of the area and reflect the endeavours of its owners and publicans. In progressive steps the pub, starting on a small corner plot, would be expanded to include adjacent properties, eventually creating both the large vault that would become the main venue of Band on the Wall and the complex of spaces that is now a hub of musical, social and learning activity.

Figure 4 – The expansion and changing numbers of the George & Dragon

It is hoped also that this first part of the history, relating to the 19th century, conveys something of what life was like for the people of the area, of the issues affecting them and of the music that was part of their lives. This is not intended as an academic work; it touches briefly on many topics and, hopefully, provides some routes for readers who wish to explore these subjects in greater depth. The document also will be adapted over time in the light of fresh information and readers’ comments and amendments.

Footnotes

1 Neil Richardson, letter to Brian Holmshaw, 28.6.2000; Alehouse Recognizances, County Record Office, Manchester.

2 ‘Memories of New Cross’, article in Manchester City News, 2.10.1920.

3 Peter Hall, ‘The First Industrial City: Manchester 1760-1830’, 1998.

4 Manchester City Council website – ‘Manchester Firsts’

5 Eric Hobsbawm. ‘Industry and Empire, from 1750 to the present day’

6 Peter Maw, Terry Wyke & Alan Kidd, Economic History Review (2011) ‘Canals, rivers, and the industrial city: Manchester’s industrial waterfront, 1790-1850,’

7 Bristol-born, Oxford-educated poet and historian Robert Southey, ‘Letters from England’