Appendix 1

Appendix 1

New Cross: Scene of Riots and Agitation

The new cross was an important meeting point for traders, travellers and carriers, as well as a ‘rendezvous where all kinds of opinions could be ventilated: politics, socialism, religion, literature and multitudinous other subjects’.1It also was an open market. By the late 18th century the District was called New Cross.

“New Cross was a moderate open space, the centre of four important thoroughfares at the bottom of Oldham Road, with Oldham Street on the south, Ancoats Street on the east, and Swan Street on the west. It is ground sacred to the people, having been consecrated by their blood in times past, through the Bread, Weavers and Reform Riots that took place for the amelioration of the working-class conditions’.2

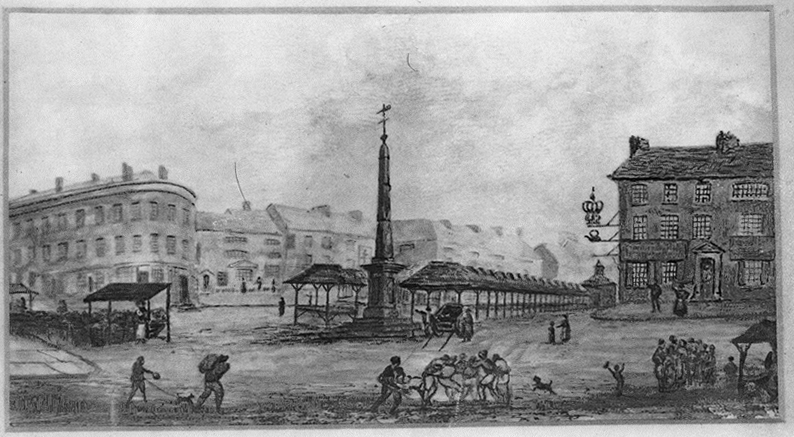

The above drawing of New Cross, drawn around 1820, apparently from close to the site of the present Frog & Bucket Comedy Store, shows the numerous stalls lining up Oldham Road and with goods and provisions for sale and distribution by cart throughout the town and beyond. This was a street market, mainly for meat and vegetables, that moved to the Smithfield Market shambles in 1821.2

On the right can clearly be seen the Crown & Kettle pub, still extant in a modified form at 1 Great Ancoats Street, and the building on the left side in Swan Street displays the curved frontage the style of which is retained in the present HBL bank building on this site. Two groups of people are drawn: on the right perhaps a discussion group of some kind; more centrally in the picture, fisticuffs appear more to the fore; perhaps the participants had overdone it in the Crown & Kettle where in 1820 a Tom Richardson was publican.

In 1823, a correspondent in the Manchester Chronicle referred to trouble outside the Crown & Kettle, and two pubs in Oldham Road:

‘At the ends of many streets stand groups of Irish ruffians who appear to feel no interest but in ill-treating the peaceable and unoffending inhabitants.’

This is particularly the case at the following places – near the Crown and Kettle, the Briton’s Protection and the Death of Nelson… violence is common and many depredations are committed’.3

The Manchester City News article1describes the lively group discussions at New Cross, ‘a place where the poison of discontent could flow freely, where wrongs were proclaimed and remedies suggested, and hopes entertained of their realisation’.

During Bread Riots in the early part of the 19th century, ‘there were frequent conflicts between the military and the people. Cannons were placed so as to command the four thoroughfares, where shots were fired from cannon and small arms, thus wounding many of those assembled and other innocents thereabouts’.

Another history article describes the bread riots:4

‘The neighbourhood of New Cross had some exciting experiences in connection with the distress of 1795-8. War was raging on the Continent, food was scarce and dear, and little work was to be got. Hunger and misery were widespread, and bread riots resulted. On July 31 matters reached a climax and the Riot Act was read. All persons found in the streets were required to give an account of themselves, but in spite of all precautions a hungry crowd attacked several carts loaded with meal at New Cross, and it was only when mounted soldiers appeared on the scene that the crowd dispersed.

‘History repeated itself in 1812, and on April 20 a cart loaded with meal was stopped at New Cross and the contents of sixteen sacks were distributed by a crowd of hungry men and women… quiet was not restored until the Riot Act had been read and the cavalry had been marched down Oldham Street’.

The ‘Cholera Riot’

An article by John O’Dea in the Manchester City News of 18.2.1905 describes the New Cross Cholera Riot of 1832 that followed the death from cholera of a young boy who had died in the hospital in Swan Street. The child’s grandfather opened the coffin in the graveyard and ‘to his horror found that the child’s head had been severed from its trunk and a brick put in its place!’.

‘The rumour immediately spread that a child had been murdered at the Cholera Hospital. During the day a great crowd of frenzied men and women visited the cemetery. They took the coffin out of the grave, tore off the lid, and the mutilated corpse was exposed to the gaze of the horrified spectators.

‘The Burke and Hare murders were still fresh in the memory of the public. A cry instantly arose, ‘Burkers! Burn the Hospital!’ The mob shouldered the corpse and made way to Swan Street. On arriving at New Cross the dimensions of the excited crowd had swollen ten-fold. They marched to the Hospital, forced the gates, and immediately set about demolishing the premises. Chairs, tables, beds and other articles of furniture were thrown into the street and broken to pieces. The Hospital van was dragged out, set on fire and destroyed. The doctors and attendants had warning of the coming of the mob, and thus were enabled to effect their retreat in safety. The patients, to the number of 28, were removed by their friends, but one man, who was in a state of collapse, died the same evening. The police at the adjoining Shudehill lock-ups – at this time numbering no more than 20 men – were powerless to cope with such an infuriated mass’.

Eventually a young Irish priest intervened and addressed the crowd, explaining that only one individual was to blame: a medical attendant who had removed the head with a view to selling it for dissection, without the knowledge of the medical board. The crowd took the priest’s advice and returned to their homes. But ‘the men, however, who had carried the coffin from the graveyard had, in the meantime, decamped with their gruesome burden down Oldham Street, demanding money from those who wished to obtain a sight of it’.

A ‘strong force of special constables’ eventually took the body to the Town Hall where a surgeon re-attached the head to the body and the following day a re-interment took place, attended by ‘an immense concourse of people’.

Evil Spirits

Another gruesome fact about New Cross is that early in the 19th century excavation work at the site revealed numerous human remains. These were the bodies of suicides and hanged criminal from a previous era. It was the practice to bury the bodies of suicides and hanged criminals at the town or village cross, and with a wooden stake through each body. This ancient practice was believed to allow evil spirits to escape from the dead bodies, and the crossroads location providing four escape routes.