To give an adequate introduction to Miles Mosley is no mean feat. A renowned bassist, composer and arranger; he, like his comrades in The West Coast Get Down, has been sought after by the industry’s foremost artists and producers, since committing to a life of professional music in the early two thousands. His side work with Ms. Lauryn Hill, Mos Def, Joni Mitchell and Christina Aguilera didn’t thrust him under the spotlight, but it saw Mosley’s name scrawled into many a record producer’s notebook and opened the door to a world of musical possibilities, which today includes scoring video games, film and TV projects, composing for prestigious dance companies, producing the work of other artists and co-designing signature music equipment.

When Mosley is centre stage, his inventive upright bass work is at its most arresting. He is to the upright bass what Tom Morello is to the electric guitar; a technical virtuoso utilising available technology and effects to take his instrument beyond its once accepted limits. Pair with that his soaring vocal and a penchant for retro arrangements and you have an artist comparable in style to early seventies Edwin Birdsong, with shades of Jimi Hendrix and a firm jazz rooting in the acoustic bass styles of musicians like Ron Carter and Richard Davis.

To complete his introduction, you need make the acquaintance of The West Coast Get Down; a Los Angeles-based collective whose core members, in addition to Mosley, are drummer Tony Austin, saxophonist Kamasi Washington, trombonist Ryan Porter, pianist Cameron Graves, drummer Ronald Bruner Jr. and keyboardist Brandon Coleman. Individually, they’re some of the most outstanding musicians on the West Coast, possibly throughout the U.S., yet their stories begin with the same neighbourhoods and music institutions.

“I’ve known the members of the West Coast Get Down since I was in High School” Mosley explains, “we all grew up together in Los Angeles, CA, and I feel that is a particularly fortunate position [for us] to be in: one that allows the music to open up in a manner that is almost telepathic. We share so many of the same influences, and are so familiar with one another” he elaborates, “I truly think of each of them as brothers and love them all dearly”.

The musicians of the WCGD pervade popular music. The string arrangements and bass on Chris Cornell’s Casino Royale Theme, You Know My Name: written and performed respectively by Miles Mosley. When Willow and Jaden Smith take to the stage, Tony Austin is often at the kit. The saxophone on Ryan Adams’ Gold: Kamasi Washington, the synths on Dornik’s debut single Strong: Cameron Graves, the trombone on Nick Cave’s Higgs Boson Blues: Ryan Porter. Their success as session players was irrefutable, but they needed a project to call their own.

And so the WCGD began, in earnest, with Mosley identifying that need to “create a home for us when we were off tour to work on our music”. Collectively, they’re a well-oiled machine, brimming with such bold and inventive ideas that it’s a wonder they ever contained themselves as “sidemen”. They assumed their name during a club residency in Hollywood, as Mosley explains. “We were playing this little club that we would pack to capacity every Wednesday and Friday. We were able to really build our repertoire and get a feeling for this new sound we were going for, one that was filled to the brim with energy and really hard hitting solos. At the beginning of each night I would shout, “Ladies and Gentleman, welcome to THE west coast get down, your Friday night DJ alternative!” Something about the phrase stuck in people’s minds as a moniker that represented energetic live music”.

Through their Hollywood residency, it became obvious that ‘the Get Down’, moving with fluidity and ecstatic with ideas, could pool their talents and resources, and embark on an ambitious recording project of virtually unprecedented scale.

“Logistics is a specialty of mine and Barbara’s, Tony is a great general… Kamasi is a solid motivator”, Miles explains. “These things combined to create the perfect conditions for high impact recording”.

Discussing their sessions, Mosley lays out some cold, bare numbers: “10am to 2am, every day for 30 days, 170 songs.” The group had decided to hire a Los Angeles studio for a solid month of recording sessions. They tackled a set of compositions from each of the Get Down’s core members: Kamasi Washington’s large-ensemble arrangements, Miles Mosley’s bass-led R&B, Cameron Graves’ hard-edged, classically-inclined jazz… no stone was left unturned and no musician went home empty-handed. “The sessions that produced all these WCGD albums were done at a breakneck pace”, Mosley admits. “None of it would have been possible without Tony Austin, our drummer and Engineer. He’s like the “Danger Mouse” of the WCGD. Each one of us brought something to those sessions that helped to make the magic happen. I brought a serious set of organizational skills, Kamasi was really good at getting everybody to agree to the sessions and clear their schedules, our manager Barbara Sealy (who’s known us since we were 13) made sure we had everything we needed to be creative. It was a once in a lifetime opportunity and we really made the best of it”.

“We ran the sessions closed: no photos, visitors, girlfriends, labels, nothing”.

In the spring of 2015, their hard work began to pay dividends. Kendrick Lamar’s album To Pimp a Butterfly, upon which many of the WCGD and their extended L.A. family, including Terrace Martin and Stephen ‘Thundercat’ Bruner featured, took the music world by storm. It united rap fans and finicky musos, saw the influencers: the likes of George Clinton and Snoop Dogg, working with those who drew influence from them as young musicians and was ultimately acknowledged as an album for the ages. It was the finest precursor to the release of The Epic, that Kamasi Washington and The West Coast Get Down could’ve hoped for, as it brought the first album to be released from their month of sessions to international attention. An audience were poised to hear from the musicians who had driven Lamar’s opus in such a distinctive musical direction, given it depth and musicality. The Epic knocked that audience back with it’s sheer enormity. 172 minutes of music, more than fifty auxiliary musicians and choir members in addition to the West Coast Get Down, who’s rhythm tracks are the core of the record. Like To Pimp a Butterfly, it quickly became an album of the year contender.

Looking back on the time frame when To Pimp a Butterfly and The Epic were released, Mosley explains “I am very grateful to Kendrick for acknowledging the supreme talents that are on his album and shining a light each of them individually. TPAB really helped to fuel The Epic. Since we all began making these albums at the same time we all share a sense of responsibility for their success. When we saw that The Epic had the opportunity to catch fire, everybody in the WCGD invested their time and energy into heavy touring with Kamasi. I think each of us knew that the bigger we could make that album the better off all of the other WCGD albums and shows would do. Touching on the possibility of history deeming it a ‘golden era’ for L.A. music in years to come, Mosley admits it would be “a fantastic legacy” but felt it remained to be seen.

Further discussing his City’s music scene, he says “I do think that the ever roving, slow moving spotlight of the musical lexicon has shone upon Los Angeles once again. Every city has its turn in the darkness, an incubation period in which artists dive deep to create a scene that is unique to them, and eventually the spotlight hits it, and all the hard work pays off. It is our responsibility to not let up, to keep pushing ourselves to create at a high level. Whatever our legacy may become known as in the future, it is far from complete at the moment”.

The urgency to move forward sees Mosley’s debut record, Uprising, become the focus of The West Coast Get Down’s activities in 2017. A vastly different album to Kamasi’s, its unassuming, soulful styling and subtle arrangement allow for Mosley’s bass to lead prominently. The difference is evident on stage too. “When it is my turn to front the WCGD I set up the stage differently from Kamasi and the others” Miles explains. “I bring the rhythm section from the back of the stage to the front. Drums and Piano right up front, and slide the horns back. I find it important to keep that dynamic in place. Then sanctity and connection of the rhythm section is what makes all of this music feel so special. Improvisation and groove is at the center of what we do no matter who’s project it is, so having my groove machines near by is really important”.

Rhythm inevitably drives Mosley’s music, but it’s also very nuanced and allows for Mosley’s unique expression on bass. “It has been my life’s goal to demonstrate how powerful the upright bass can be from center stage. I have taken note of all the greats who have come before me and put my spin on it. I’m very comfortable on stage and on a microphone and in the end the dynamic of the WCGD comes down to one thing, energy”.

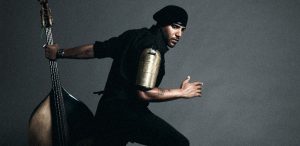

“I like monochrome looks, and timeless objects”.

With his signature Blast Cult One4five bass, his beret, black shades and shoulder armour, Mosley cuts a figure you would march to musical war behind. “When it comes to fashion I am a utilitarian” he admits, “I like monochrome looks, and timeless objects. The beret and armor sit well with this album and the attitude I have on stage, which is to revolutionize the Upright Bass and inspire people. I’m always impressed with artists like Janelle Monae who express themselves through fashion. It’s a wonderful art form and I have an immense respect for the fashion industry”.

Mosley’s modesty and compassion ensure his musical collaborators and mentors are praised alike. “I have been the beneficiary of a tremendous education from some truly selfless and generous teachers” he avows, “sometimes I feel like a formula one racecar” he laughs. “I am the sum of a lot of tinkering hands; specialists in a multitude of skills ranging from classical studies, jazz studies, humanities, etc… education is the key to EVERYTHING. Not just music, but the very fabric of society relies upon a diverse education, it is how we build understand and compassion”.

He has very clear ideas surrounding education and the opportunities he has been afforded, as well as thoughts about how his experience might help other young people. “I believe that the conditions of a culture are always directly reflective of the quality of education, and the extent to which people have free access. Music education is an interesting beast. Were I able to wave a magic wand, every child on earth would receive a competent and applicable musical education from the age of 3-10. The goal would not be to create a legion of musicians, but to allow the study of music to work its magic on a developing mind. This type of societal norm would benefit mathematics, critical thinking, team work, and community to name a few. Additionally, the society’s appreciation for the truly talented that arose from this education and continued along the path would rise, because everyone would have first-hand experience with the kind of effort and discipline it takes to be a musician, let alone, an artist”.

Mosley’s vision of mass artistic development mirrors the grandeur of the Get Down. A collective to whom hard work has paid dividends, they’re all eager to share in the music and the joys it can bring. Aside from the Get Down, Mosley’s passions and joys extend from scoring films to rounds of street fighter and heavy reading. Discussing his latest film project, a score for director Ben Caird’s Halfway, which among other things, addresses America’s judicial system, Mosley explains “I really enjoy scoring films, it is a true passion of mine, and the marriage between music and visuals is an investigation with which I am enamored. “Halfway” takes a circuitous route to touching on a very sticky subject in America. It is my goal to support the emotion on the screen and guide the films subtext as effectively as possible. I’m proud of that score and the somber, yet beautiful nature of the compositions”.

Having signed a deal with Verve/UMG, “a dream come true!” you can expect to hear much more from Mosley, be it stage, screen, video game or recording, over the coming years.

Make sure you catch Miles Mosley and the collective of musicians on the upward curve, making their Manchester debut at Band on the Wall on 30th June. If you don’t walk out whistling Abraham, then you just aren’t getting down hard enough!