In recent years, Mali, like other Francophone West African countries, has had its share of hip-hop groups. A rhythmical, poetic, dynamic and uptempo spoken lyric, providing social comment over music, is hardly a new idea in Malian music. It’s one that’s many centuries old, in fact: the elder male griots used a similar method to narrate events and epics, as do also the fune, a special group of Mande artisans dedicated exclusively to performance of the spoken word.

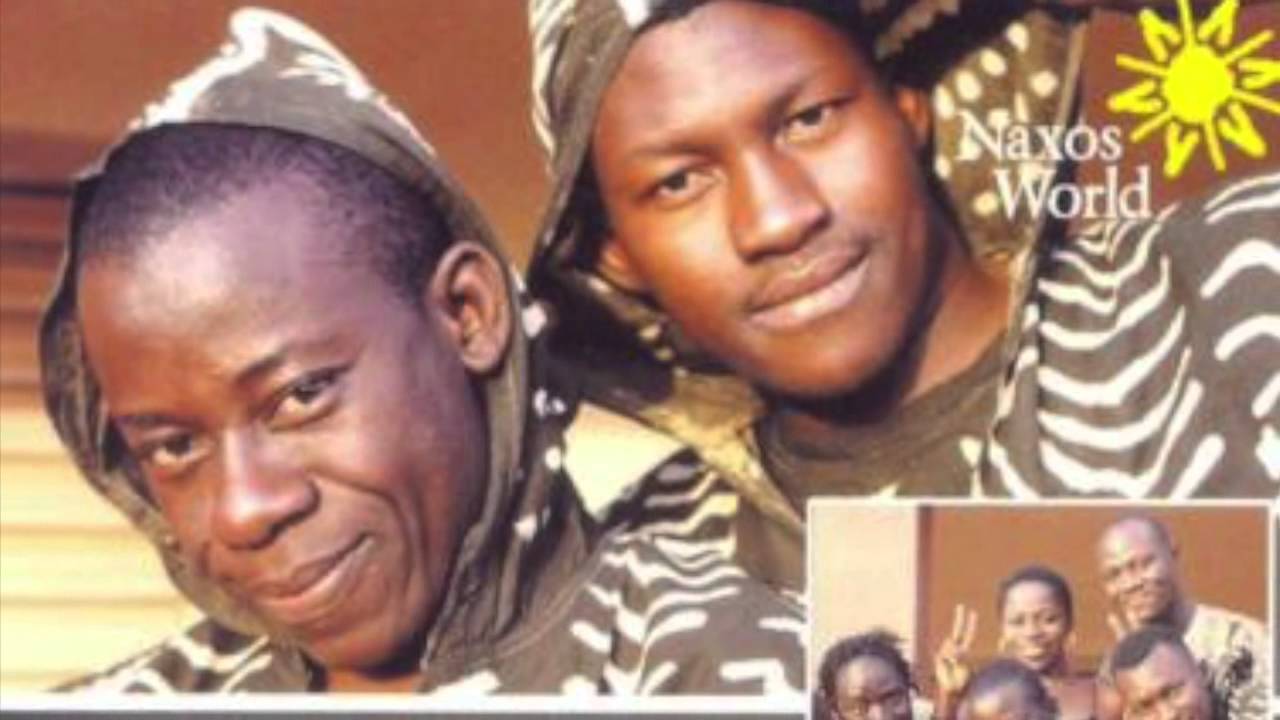

Two of the pioneering and most influential and successful Malian rap groups are Les Escrocs and Tata Pound. Les Escrocs are not a typical rap group in that they use a live band of jeli instruments and the music and choruses are clearly in the jeli style. Tata Pound are three youngsters from Bamako who rap in Bamana, and work in a more mainstream style using a backing of samples with hip-hop and reggae sounds, and are noted for their outspoken criticisms of the government. Their most recent album, Cikan (Le Message), includes a collaboration with Ivorian reggae superstar Tiken Jah Fakoly and a cover version of Salif Keita’s Prinprin. Fakoly himself has similarly bold lyrics, and his criticising of corrupt politicians in his native Côte d’Ivoire forced him to flee the country. He is now settled in Bamako, where he has opened a studio. He is enormously popular among the youth and is single-handedly reviving interest in reggae.

The trend in Mali at present is towards smaller, semi-acoustic groups featuring mainly traditional instruments, such as those of singers Kassé Mady Diabaté and Habib Koité, kora players Toumani Diabaté and Ballake Sissoko, and Djelimady Tounkara. They all draw primarily on the celebratory jeli style, such as one might hear at a wedding party, although their experiences of collaborating with international artists bring a new, more contemporary perspective to the tradition. The cross-fertilization between “traditional” wedding music and modern music is inevitable, given that many of the musicians play in both domains. Kassé Mady Diabaté is arguably as mighty a singer as Salif Keita, though more rooted in the jeli tradition. His 1988 album Fode was meant to be an answer to Soro but did not get much press attention. His second album for the Paris-based producer Ibrahim Sylla, Kela Tradition (1991), an all-acoustic recording of some of the classic jeli songs, showed this to be his true forte, as further demonstrated in his 2002 album Kassi Kasse, recorded on a mobile studio in his native village, Kela. He has since gone on to participate in Sylla’s fine album Mandekalou.

One other important trend in Mali since the mid-1990s has been a new interest amongst the urban youth in the balafon music of the Senufo people from the south of the country. The lead performer of balani is Neba Solo, a brilliant player and singer who has adapted and modernised the tradition by adding bass notes to the xylophones to fashion a more pronounced bass line.