The dance format that stormed West and Central Africa before and after World War II was the Afro-Cuban rumba. Itself a new-world fusion of Latin and African idioms, the rumba was quickly re-appropriated by the Congolese, most notably by adapting the piano part of the son montuno to the guitar and playing it in a similar way to the likembe or sanza thumb piano.

Although Ghana’s highlife pipped it to the post as the first fusion dance music with pan-African appeal, Congolese music was less influenced by European taste than highlife and it was in many ways more African, even though Western instruments were used. The forefathers of Congolese popular music included the accordionist Feruzi, often credited with popularizing the rumba during the 1930s, and the guitarists Antoine Wendo Kolosoyi, Jhimmy and Zachery Elenga. These itinerant musicians entertained in the African quarters at funeral wakes, marriages and casual parties. In more bourgeois society, early highlife, swing and Afro-Cuban music were the staples of the first bands to play at formal dances where the few members of the elite “evolués” could mix with Europeans.

A few early greats, such as Jean Bosco Mwenda from Katanga – who was recorded in the field by the South African musicologist Hugh Tracey and later made his career in Nairobi – blazed a trail in Congo’s eastern regions. But most of the key developments took place in Kinshasa, whose population swelled after World War II, with huge numbers of Congolese attracted to the city by well-paid work, public health and housing – and by its reputation as a “town of joy”.

In Kinshasa, life was cosmopolitan: French-style variété, or cabaret music, made its mark, while other ingredients which combined to form the classic Congolese sound included vocal harmonic skills learned at church and, later, a tradition of religious fanfares played on brass-band instruments.

Besides its inherent musical appeal – not least its ability to sound both mellow and highly charged at the same time – the cross-border popularity of Congolese music was boosted by a number of practical factors. First, it was “non-tribal”, making use of the interethnic (and very melodic) trading language of Lingala. Second, the distinctive guitar style was an amalgam of influences from the Central African interior and the continent’s west coast. Third, the music also appeared in the right place at the right time. The postwar Belgian Congo was booming and astute Greek traders in Kinshasa saw the commercial potential of discs as trade goods to sell alongside textiles, shoes and household items – including, of course, record players.

Inspired by the success of the GV series of Cuban records distributed by EMI, the early Congolese labels – Ngoma, Opika, Esengo, CEFA and Loningisa – released a deluge of 78rpm recordings by semi-professional musicians of local rumba versions alongside releases of folklore music. Radio Congo Belge, which started African music broadcasts in the early 1940s, provided the ideal promotional medium. While live performance remained more informal, the record companies maintained their own house bands to provide backing for singers. The CEFA label employed Belgian guitarist and arranger Bill Alexandre, who brought the first electric guitars to the Congo and is credited with introducing the finger-picking style. The rival Loningisa label recruited Henri Bowane from the Equatorial region, who injected even more colour into the style.

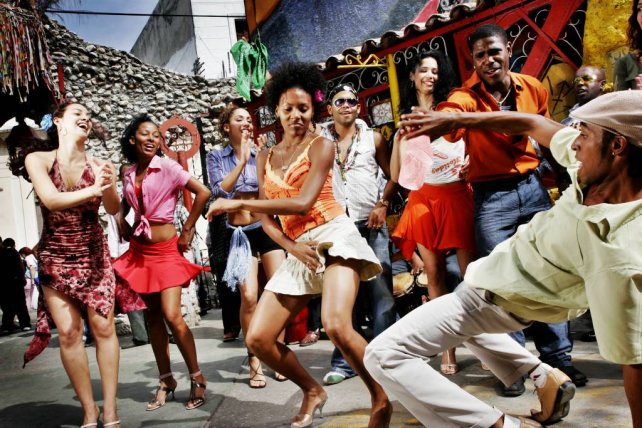

Header image: Jazzuary