Grammy award-winning percussionist Lekan Babalola is an inspirational character and one conversation with him can leave you with endless avenues to explore. An intelligent multi-disciplinarian, Babalola’s music has benefitted from a life of tremendous experience – he has seen many cultures and studied in many areas, each informing the way in which he approaches his music and his lifestyle. He has played percussion for a host of internationally renowned artists, but through his solo projects explores work which relates more closely to African cultural tradition. Ahead of his show at Band on the Wall in July, we spoke to Lekan about the Sacred Funk project, his thoughts on European and African culture and his early life.

Your musical development began in the church; how did that environment and the influence of your father help shape you as a musician?

The church environment and the influence of my father helped to shape me as a musician. It emphasised the discipline of constant playing everyday of the week and also your role as a musician, because you were playing for the church services and were part of the choir/drummers and congregation. It was led by my father, Olayiwola Babalola, who was an accordionist and he would always be telling everyone to “listen”. It wasn’t about ego it was about music being sacred.

You’ve been leading bands and recruiting musicians for ensembles since your childhood and it’s clear that you’re a confident and creative leader. When did you first recognise your qualities as a leader and do you think they have helped you in forming groups like the Sacred Funk project and Eko Brass Band?

My Father used to have me sitting with him playing drum or cowbell during his composition sessions and he would often ask me if I like the song he is working on. From there I had the idea of how composition and arrangement of music pieces is done. I would try to imitate my Father when I had my friends in my house and suggest ideas to them, which sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t.

It’s not until you get older that you fully realise the influence of these childhood experiences, however what consolidated it all was the experience of watching artists, such as Michael Jackson and spending time with Fela Kuti at the Shrine, not playing in the band but talking politics. Later on my experiences of being with many Art Blakey as a PA informed my approach to music and musicianship. This gave me confidence to begin creating my own projects as an artist. Collaboration with other artists has always been my motto.

You first came to the UK with an engineering scholarship, prior to making music your life’s pursuit. Have you retained other academic interests aside from music since that time?

Yes, I studied filmmaking at Central St Martin’s College of Art and Design London and Northern School of Film & Television in Sheffield and I founded the Ifa-Yoruba Contemporary Arts Trust in 1995 to foster the development of Yoruba arts, particularly its relationship with the African Diaspora and culture, and encourage this re-connection to ourselves through contemporary Art.

I am an art Curator and use this medium to learn about my own cultural history and how it intertwines with many other cultures. I also practise my traditional belief system of Ifa and am currently working with Dr Olu Taiwo on a translation of the Ifa verses into performance poetry.

How did the Sacred Funk project begin and can you tell us a little about the musicians you chose to be a part of the project?

Sacred Funk project began through my collaboration with musician Kate Luxmoore, who introduced me to sacred European music and later to her own heritage of English folk music. This was then consolidated when I lived in rural South West in Dorset and Somerset and also began to learn about ancient traditions from there. The music is a combination of my traditional culture and those that have encountered. I also felt a need to create a band that could help to re-connect musicians together to share the sacredness of the music itself.

I continue to work with Kate Luxmoore from the classical and folk worlds, Alvin Davies is a saxophonist drawing on gospel and reggae genres, as does Pete Reed on Bass. The two younger members of the band draw on a very broad range of styles, Reuben Reynolds the guitarist is a funk and pop player but with an innate ability to diversify his playing and Christos Styliandes is a Jazz trumpeter. John Silky is a jazz funk drummer who is also a great composer and these skills combined bring a wealth of sounds and ideas to draw on.

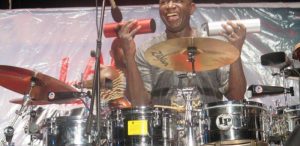

No two percussionists have an identical setup; what equipment goes into your setup and do you have preferences for what achieves the greatest sound?

My set up is different according to what gig I am playing. On Sacred Funk I play far more congas, bongo, Cajon and a rig of cow bells, wood blocks, chimes, cymbals and shakers. On other gigs I might play lesser known drums such as Sakara (indigenous Yoruba pre-talking drum) and bata, which you would hear currently mostly in Cuba.

I have a brass band in Lagos called “Eko Brass Band” and I play mainly timbale and electronic percussion pads, as I have 4 percussionists in this band who play military drum and sakara. It’s all about the sound of the different skin and percussion textures. I like to experiment with sound, particularly in a recording situation, and often try layering multiple sakara of different sizes (there are 6 sizes) to create new possibilities.

Musicians draw inspiration from many different things, what inspires you to continue creating music and exploring new sounds?

What inspires me is my tradition but also the cultures which I inhabit. My children inform me with new ideas every day and keep my brain young, going back to childhood your antennae has to be open! Travelling with gigs and other bands around the world also helps to keep my mind broad, so I make sure if I am on the road that I visit places and take an interest in what is there under the surface and I often find that tasting the traditional food of a country informs you about the people and the culture.

African and European culture is traditionally quite different, although in modern times there is a great deal of cultural integration, but that said, do you think European culture and by extension European music, could benefit from African customs you’re aware of and maybe grew up with?

Yes. I have talked at length with Kate Luxmoore, our Sacred Funk Project MD, about this subject. We know we are one as human beings but we think very differently depending on our society. The Yoruba’s have a saying that “the fingers on our hands are not equal, but each of them is important”. For us to go forward we must unify and work with all our differences to find a reflection of us all. There are barriers to this in the way we have all been trained to think or see things. The western perception or viewpoint is linear or hierarchical – it goes from a to b, or from bottom to top. The African perspective (pre-westernisation) is fractal. It responds to things as they are needed and interconnects in a way that can look very confused from a western perspective. You hear it in the story telling, stories will go around, interconnecting with different stories until it comes full circle to end.

I think that by learning these different traits from one another we can become more integrated as human beings and also as a community. We all need each other, but we have forgotten this because we have relied on money alone.

The community I grew up in, in Lagos, Nigeria was not about money, it was about faith, trust and being together.

Get your tickets for Lekan Babalola’s Sacred Funk Project here.