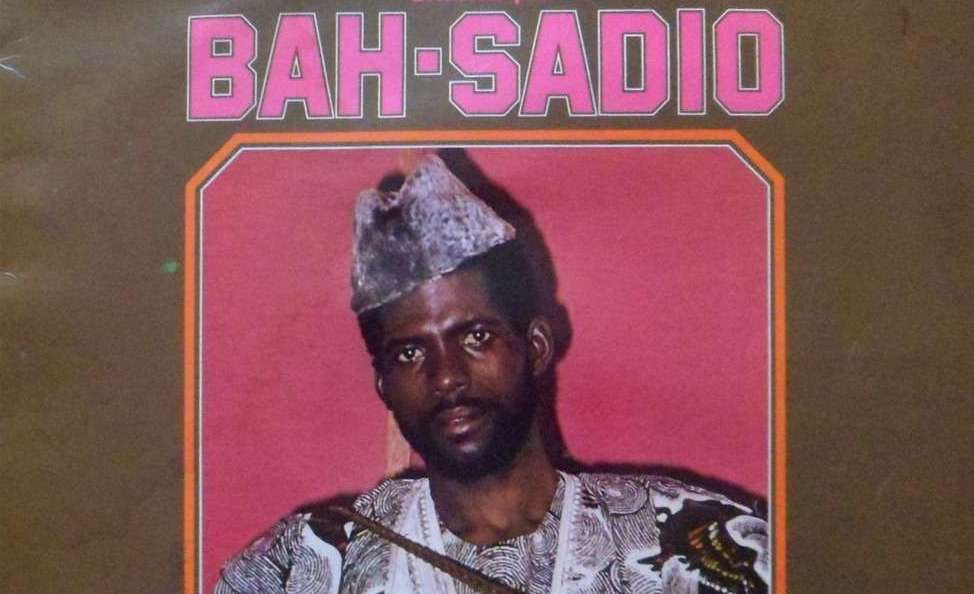

The most established names of Guinean music are to this day artists from prestigious jeli families. Yet since the mid-1990s, this prevalence of Mande music has gradually been challenged by musicians from other backgrounds, who have taken up music as a matter of choice, not birthright. The first to mark their place on the “free music market” were artists of Fula background. A handful of Fula artists had already enjoyed some success in the late 1980s, notably Bah Sadio, whose tender guitar-and-voice album Folklore Peuhl (1988) is a tear-jerker of a record, haunted by the pain of the émigré. Sadio had recorded this intimate work while in exile during the Sékou Touré years, but it had only been released in Guinea afterwards.

The most common sound of 1990s Fula pop had, however, little in common with Bah Sadio’s humble (and humbling) work. When Amadou Barry climbed to the top of the national charts in 1994 with the zouk-inspired beat, catchy accordion riff and cheeky lyrics of “Joma Galle”, the music of the nyamakala had found its twentieth century articulation. Artists such as Petit Yero, Fatou Linsan and Binta Laly Sow left their local ceremonies and the shoddy nyamakala image behind and reinvented themselves as artistes modernes. Relentless dance beats, built from typical nyamakala triplets, suave Mande zouk and fluttering flute solos paved the way to the top of the charts. The typically raunchy lyrics of their songs stemmed directly from the nyamakala tradition, and contributed largely to their success. (Mowlannan, “Rub my body” was the title of Petit Yero’s greatest hit, Bulu Njuuri, “the source of honey” by Binta Laly Sow a love ballad as daring lyrically as it was beautiful, while Sekouba Fatako’s releases are simply explicit – and sell en masse).

The one Fula singer that has consistently produced the most imaginative, deeply rooted and forward-looking works is Lama Sidibé, whose debut Falaama (1999) sold out in a matter of weeks. His second album, Séguéléré, was one of the biggest sellers of 2005. The intricate polyphonies and cross-rhythms that mark the traditional music of Guinea’s forest region have still to make their impact on Guinean popular music, though ex-Amazone Seyni Malomou, the R&B-leaning Sia Tolno and Nyanga Loramou have won some acclaim.

The most unexpected chart-toppers of recent years were two Sussu groups. Les Étoiles de Boulbinet, named after their neighbourhood near Conakry’s harbour, had the brilliant idea of combining the humble street-instrument kirin (a lamellaphone made from three iron keys attached to half a calabash), the gongoma drum, the balafon and various percussion instruments into an ensemble buzzing with the rugged ambience of inner-city Conakry. Their acoustic home production Waa Mali (1997), based entirely on the traditional rhythms and instruments of the Basse Côte, became an unexpected chart climber. It proved contagious. Soon after, a second band took the same format to even greater success: Les Espoirs de Coronthie. They made raw, acoustic music cool, and worthy of Conakry’s dancefloors. Their numerous young, dreadlocked band members lived a stunning rise from street-roaming youngsters to nationally celebrated stars over 2004, when their second album Duniya i guiri was the only music that Guineans seemed to want to hear. It nestled for weeks at the top of the charts, even stealing the #1 spot from Sekouba Bambino Diabaté.

Les Espoirs may call themselves the “hope of traditional music”, yet their approach to production and arrangement is in fact very contemporary, and indicates new avenues for Guinean popular music. In a similar vein, the Switzerland-based singer Maciré Sylla blends Mande music and Sussu vocals with smooth strands of jazz, while the quartet around kora player Ba Cissoko combines a rootsy base with the inspired outlook of a young generation searching for new routes. In 2004, the ensemble surprised the world with their debut Sabolan, an album that takes gracious kora melodies for a walk around the city and simmers with the mischievous funk only an urban griot could produce. They are one of few Guinean bands that have made a name for themselves outside Africa, and they have used their newfound success to nurture and support a new generation of Guinean instrumentalists. When they’re not touring abroad, they are busy organizing concerts back home, sourcing new artists and spreading the message that had lately been lost among many upcoming artists: that patient practice, meticulous work and the study of an instrument can ultimately be more rewarding than the quick assembly of a short-lived pop production.

Guinea has also vibrant reggae and hip-hop scenes, though the true ground-breaking works in those genres have been rare, and little has trickled beyond Guinean borders. Kill Point are the godfathers of Guinean hip-hop. They have been around since the early 1990s, and have today almost the role of mentors, organizing hip-hop festivals and supporting newcomers. Most young rappers look closely to the well-developed hip-hop scene of neighbouring Senegal, and the most successful groups, such as the female trio Ideal Black Girls and the R&B/ragga outfit Degg J Force 3, have often approached hip-hop savvy producers in Dakar to record their cassettes.

The best-known name in Guinean hip-hop abroad is still Bil de Sam, whose clever rap-version of the jeli classic “Sunjata” received some unexpected airplay in the UK.