The Publicans: 1803-1856

This continuous chapter traces the tenure of the first licensee of the George & Dragon, Elizabeth Marsh, and the subsequent licensees up to the half-century ownership of the pub by the McKennas. It also refers to the changing street numbers for the George & Dragon.

1803-1856

The first licensee of the George & Dragon

The 2007 historical research by iCosse cast substantial doubts over earlier research that concluded that the first licence for a George and Dragon in Swan Street was granted to an Elizabeth Marsh in 1803. By revisiting primary records, our current research sets aside these doubts and positively confirms that Elizabeth Marsh was the first licensee of the George & Dragon in Swan Street. In the Poor Rate Books for the street for 1804 and 1806 she is recorded as the occupant of the premises, described as a public house.

The prior uncertainty about this fact is understandable, as not only is Elizabeth Marsh’s name missing from almost all the early records for Swan Street but she is also recorded from 1794 as the licensee of another George & Dragon, some two miles away in Ardwick, and she is still listed there in 1804 when – apparently in the Rate Book only — she is recorded as licensee of the George & Dragon in Swan Street. The question must remain as to whether or not she was simultaneously the licensee of two pubs, an unusual circumstance in Manchester in this period; we have been unable to find subsequent records of her tenancy of the George & Dragon in Chorlton Row, Ardwick. Certainly she was there for at least eight years but her occupancy of the Swan Street pub would be much shorter: she gave up the licence in 1807.

It would be 117 years before a woman would once more be licensee of the George & Dragon on Swan Street, and then only on the death of her husband.

We know nothing of why Elizabeth Marsh gave up the license, nor where she then went; the only subsequent, possibly relevant, record we have found for an Elizabeth Marsh at this time is a widow in King Street, Salford, in 1808/9.1

The 2nd Landlord: John Roberts

Elizabeth Marsh’s three-year tenure at the George & Dragon came to an end on 28 January 1807 and the licence was transferred to a John Roberts.2 Placing this in historical context, this was just two years after the battle of Trafalgar and more than a decade before the birth of Queen Victoria.

John Roberts, victualler, George and Dragon, 9 Swan Street – Dean’s Manchester Directory 1808/9

It is possible that this is the same John Roberts who in 1797 was the landlord of the Two Brothers inn at 30 Oldham Street, within a few hundred yards of the George & Dragon in Swan Street. Another possibility is that he was the John Roberts whose name appears in the Rate Books for Swan Street from 1796 to 1802. It is likely that his house was amongst a scattering of small dwellings on the opposite side of the street, beyond the Shudehill Pits, that were in a separate District from the George & Dragon. These dwellings appear to have been unnumbered but are recorded for convenience in the Poor Rate Books as being in Swan Street, close to where Cable Street would be subsequently laid out. This John Roberts must have known the George & Dragon, living as he did probably within 100 yards or so of the pub. By 1804, the year after Elizabeth Marsh opened the George & Dragon, his name is no longer recorded in the Rate Book. Had he moved into accommodation at the pub and, within three years persuaded the landlady to transfer the licence to him? We may never know, though it is certain that by 1807 Elizabeth Marsh was no longer recorded at the address; John Roberts was, and he now held the licence.

In his first year of tenure, perhaps surprisingly, Mr Roberts does not appear to have used the drinks licence: the property is just recorded as a house.3 Maybe he was making improvements to what was almost certainly built as a modest dwelling. Or perhaps the house was not yet obviously a pub and it was to his financial advantage in his first year as landlord that it be assessed as a house?

Was he also related to a Joshua Roberts, victualler, Spread Eagle, 33 Church Street – also a few hundred yards away – who is listed in the records from 1814 to 1822. (Into the 1830s, an Elizabeth Roberts, presumably Joshua’s widow, was the licensee of the Spread Eagle at this address). And did the same John Roberts expand his empire by taking over the license of The Griffin, 11 Griffin Court North, Salford, as is suggested by the listing for a victualler of this name at this address in 1819-20, and operate as a brewer at 13 New Street (probably at Miles Platting) where a John Roberts is listed in 1824-25?

However, the surname Roberts and first name John were, and remain, very common names in Manchester and elsewhere in the UK, so there must be a high degree of uncertainty about these speculations. What is certain is that the reign of John Roberts at the George & Dragon in Swan Street was a long one: at least until 1825 and possibly until 1828 when the next licensee, a John Foster, is listed, to be followed by Thomas Scruton in 1836. But is this George and Dragon the same building or on the same site as the present Band on the Wall?

The changing street numbers

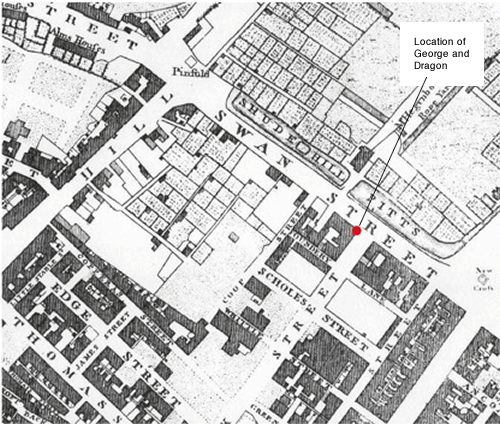

The answer to this question is far from straight forward, mainly because of the changing street numbers for the pub in this period when the Industrial Revolution was almost literally gathering steam and there was intensive building construction work in the area. We have been unable to find any maps with the numbers of the addresses in Swan Street, nor any record of the re-numbering of the street which undoubtedly happened. But clues lie within the trade directories.

The directories for this period reveal the following addresses for the George & Dragon in Swan Street between 1803 and 1836:

1803 No 9

1824 No 12

1828 No 16

1836 No 25

What are we to make of this? Was the public-house relocated every few years and on different sides of the street? What is much more likely is that all these numbers refer to the same site, the existing site of Band on the Wall (or at least part of that site), with the premises being re-numbered as more buildings were constructed in the early decades of the century.

A significant change in the streetscape must have occurred when the Shudehill Pits, situated along the north side of Swan Street, were filled in. These pits are described by iCosse:

‘Sometime in the late-1700s the lord of the manor, Sir Oswald Mosley, converted these ponds into reservoirs for the town water supply. The water was raised from the River Medlock at Holt Town by means of a pumping engine, and was conveyed by pipes to the Shudehill Pits. Richard Arkwright’s mill in Miller’s Lane also relied on the water supply from these ponds.’

Inevitably the existence of these ponds prevented the construction of buildings on that side of the street – the opposite side from the existing Band on the Wall – apart perhaps from a few unnumbered dwellings north east of the pits. Thus in the early 19th century the buildings on Swan Street only existed along the south side, where the present Band on the Wall is located. Therefore at this time the street numbers followed a straight sequence – 1,2,3 etc – all on the south side of the street but after buildings were constructed on the opposite side, a re-numbering would have been required, with odd numbers on the south side and even numbers on the north side. It is evident from the street directories and maps that a significant re-numbering of Swan Street must have occurred between 1832 and 1836; hence, we understand, the street number (not the actual location) of the George and Dragon changed from No 16 to No 25.

This is supported by the 1832 and the 1836 directories that show a similar change in street numbers at other addresses in the street, in particular we see that the 1832 directory lists a Patrick McKenna, warehouseman, at No 25 Swan Street whereas by 1836 he is listed at No43.

The surname McKenna would be vitally associated with the operation and development of the George and Dragon for over half a century and for this reason this listing in Swan Street received special attention from the previous researchers who assumed that the 1832 listing for Patrick McKenna at No 25 was ‘the first definitive evidence for the site’ [of the present Band on the Wall] and that by 1836 McKenna had moved up the street to No 43. Our contention is that this is incorrect: that in 1832, 25 Swan Street was further up the street than at present, probably on the site that is now occupied by the Mayor Mackie Smithfield Market Hall (built 1857/58) and that Patrick McKenna, like the George and Dragon, did not physically relocate; rather the premises remained the same, only the numbers were updated, with the even numbers on the newly-built north side of the street. This is more precisely supported by the fact that a James Slater, corn dealer, who in 1832 at No17 was next door to the George & Dragon at No16, was by 1836 at No27 — still next-door to the George & Dragon at No25. (Pigot’s Directories for 1832 & 1836)

So our current research suggests that Patrick McKenna’s residence at 25 Swan Street was not at the corner of Swan Street and Oak Street (the Band on the Wall site) and he may have had no connection with the McKenna family who would be crucial to the future of the George and Dragon. But of this, more later: Chapter 3, The McKennas.

Our research does suggest that the George & Dragon, from its inception in 1803, was at the corner of Swan and Oak Streets, with changing street numbers until 1836 when it was listed as No 25 Swan Street.

Subsequent records present a complex picture of the configuration and development of the buildings that comprise the present Band on the Wall. For this reason, a separate section of this document is devoted to this subject. See Chapter 4, The Buildings.

Landlord No 3: John Foster

The name that would take the George and Dragon into a new era was John Foster who by 1827, at the age of 35, had taken over the pub from John Roberts. It is not known if this was the same John Foster who in 1819/20 was a brewer at 19 Ashton Lane (Sale?), or related to a Susannah Foster who lived at 3 Swan Street in 1813. Neither is it known if he was related to a George Foster who ran the White Hart inn at 43 Long Millgate, Salford, around the same period.

During John Foster’s tenure at the George & Dragon, the town would at last have its own Member of Parliament. Though perhaps of more practical benefit to trade at the pub would be the introduction of horse-drawn omnibuses from 1825.

Oak Street annexe?

It was, indeed, a new era for the George & Dragon because for the first time the pub included nearby property in Oak Street. By 1828 the George & Dragon, with John Foster, as licensee, is listed at both 16 Swan Street and 20 Oak Street. It is probable that this Oak Street address was attached to the George & Dragon on part of the site of what was to become part of the main venue of Band on the Wall — the stage and dance floor area — though it would be many years before the two premises were interconnected. The licence for the George & Dragon applied to both the Swan Street and Oak Street addresses, with one the pub and the other wholesale and retail spirit vaults.

The expansion of the George & Dragon into Oak Street paralleled the development of the adjacent Smithfield Market that grew rapidly following the move by the potato market to the gardens east of Shudehill in 1820 and its official titling as Smithfield Market two years later. By expanding the business into this building in Oak Street, John Foster was probably responding to the arrival of new customers: the visitors, traders and associated workers at the Market that in the next few years would become one of the biggest in Europe.

As a pub that served the Market, the George & Dragon had extended opening hours. In the evening, the Market area became an attraction in its own right as musicians and entertainers arrived on the scene and customers looked for late bargains; Saturday night was a big night in the vicinity of the Market and in a single day in 1870 it was estimated that as many as 20,000 people were attracted to the area.4

Much later, this Oak Street annexe would have a more direct relationship with the Market as in 1910 it was described on plans as a ‘Fruit etc Stall’ (with public toilet accessed from the street) on the ground floor, with four store rooms on the upper floor.5

By 1836 John Foster’s tenure at the George & Dragon had come to an end. He had steered the business through most difficult times, including during the cholera epidemic of 1832 when 924 people died in Manchester & Salford, including many from nearby Angel Meadow. In the Directory for 1836 he is recorded as a spirit merchant at 36 Oak Street and in 1843 as a fent* dealer at this address and a pawnbroker at 10 Foundry Lane. The Census records for 1841 show John Foster, aged 49, pawnbroker, living in Oak Street with his 50-year-old wife Mary and daughters 15-year-old Frances and Jane (12).

*fent – dyed or printed dress, curtain or upholstery fabric or remnant of cloth

Landlord/s No 4: Thomas/William Scruton

By 1836 a Thomas Scruton had taken over from Foster and is listed as wine & spirit merchant, 25 Swan Street, though the George & Dragon name is not used in this entry. However, the pub name reappears two years later when a William Scruton is recorded as victualler, George & Dragon, 25 Swan Street. We don’t know if the Thomas and William Scruton are one and the same or perhaps related (father and son?). But by 1841, William Scruton, aged 30, whose home was in Great Ancoats Street, was still listed as victualler, as above, though a new name is also at the George & Dragon: John Schofield who is listed as the publican.

Next door to the pub was a narrow, former dwelling at 27 Swan Street — on part of the site of the current Band on the Wall main venue — and in 1836 was in an unusual dual occupancy, Edward Heath, an attorney, whose offices would have been on the first floor, with John Slater, a corn dealer, on the ground floor. A James Slater, probably John’s father, had traded also as a corn dealer from the same premises from the early 1820s.

During the Scruton tenure at the pub, an 18-year-old Victoria, of the House of Hanover, would be crowned Queen, while the final vestiges of feudalism would be removed from the town when in 1838 the Borough of Manchester was formed with an elected town council for the first time. Previously the town was managed by a combination of manorial court, parish vestry and police commissioners established by act of parliament.6

By 1843 William Scruton had moved to the Lord Duncan inn and spirits vaults at 59 Oldham Street (some 300 yards away) but his name — an uncommon one — does not appear in subsequent county records, nor indeed the entire 1851 UK Census. Perhaps this was the William Scruton who died in Manchester in 1845; if so, he would have been just 34 years old. Was he also related (husband?) to the Mary Ann Scruton who died in Manchester six months earlier?

At this time, early deaths were common: ‘life expectancy was so low in areas like central Manchester – about 40 on average if you survived childhood, not much more than 50 if you reached 21’.7

Landlord No5: John Schofield

The 1841 Census shows John Schofield, aged 25, as publican of the George & Dragon, living there with his wife Elizabeth, aged 20. Also resident there were Frederick Taylor and Betsy Oaks, both 20-year-old servants who probably worked in the pub. He may have been related to (son of?) a John Schofield who earlier in the century8 had his house and shop a few doors down, at 6 Swan Street. In 1843 Mr Schofield remained at the George & Dragon, while at No 27 attorney Edward Heath continued to do business but John Slater’s trading place had been taken by another flour dealer, Abraham Eyre. No 31 Swan Street is the Glasgow Tavern, (later to become the Burton Arms) where Isabella Abercrombie is listed as publican.

Unlike the George & Dragon that retained the same name from 1803 to 1975, The Burton Arms had three other names at different times in the 19th century, e.g.

Burton Arms, 31 Swan Street

1843 – Glasgow Tavern*

1848 – John O’Groats Tavern

1863 – Grapes Inn

1895 – Burton Arms

*In 1847, the pub is listed as both the Glasgow Vaults AND The Grapes – probably the Vaults on Swan Street, with The Grapes at the rear entrance, facing the market at the back, on Goadsby Street.

Landlord/s No6: Deacon/Deakin

By 1845 the Schofields had left the George and Dragon and the new licensee is Thomas Deacon. Three years later the listing is James Deakin who also is listed at the Queen Adelaide Tavern, a few hundred yards away at 63 Great Ancoats Street. It is possible that Thomas Deacon and James Deakin were one and the same, and that the variation in names was due to a recording error.

James Deakin had left the George and Dragon by 1850 and is probably the beer retailer at 71 Great Ancoats Street. Around this time, the Deakins were well on their way to becoming significant players in the Manchester pub scene: they were listed at six other houses, including another George & Dragon in Bridge Street.

By 1863 a James Henry Deakin is listed as owner of the Brittannia Brewery, Broadie Streeet, Ardwick, and the Deakin family formed the Manchester Brewery Company, owning no fewer than 133 licensed houses, malt kilns and the brewery. According to Gall, ‘despite early prosperity, poor management combined with over-spending brought the firm close to bankruptcy. The Brittannia Brewery closed in the 1920s’.9

Landlord No7: William Green

By 1850, 44-year-old William Green was the new landlord of the George and Dragon. The 1851 Census shows him as living with his wife Mary Ann, aged 36, their son Edwin, aged 17, a tailor, their baby son, William, and daughters Hannah, 12, and Mary, 10, as well as two servants. A total of nine people living in what probably was cramped accommodation above the pub. The Greens’ tenure there lasted several years and by 1861 the family (with a new son, Caleb, aged 4) had moved to another pub, The Falstaff, at 21 or 26 Market Place, Manchester.

It is in 1856 that we find the name of McKenna first listed at the George & Dragon,10 though at this date the Greens remained in residence before their move to The Falstaff. The McKenna family – though they never lived at the George & Dragon — were to be of such significance to the long-term operation of the pub that they deserve a Chapter of their own: Chapter 3, The McKennas.

Footnotes

1Dean’s Directory of Manchester 1808/09

2Alehouse Recognizances for 1806/07, County Records Office, Preston

4Dave Haslam, ‘Manchester, England’ 1999 (check)

5Plans submitted to Manchester City Council, 10 October 1911

6Alan Kidd, “Manchester/Liverpool: Timeline Manchester, 1750-2002, part of Shrinking Cities project

7Peter Rushton, ‘Family Survival Strategies in Mid-Victorian Ancoats’